If you’ve heard of late release NES curio Nightshade, it’s probably by that name and not its full title, Nightshade Part 1: The Claws of Sutekh. Australian studio Beam Software clearly had big plans for this aggressively quirky point-and-click adventure/fighting game hybrid. They even managed to get industry giant Konami to take on publishing duty via their Ultra Games label. Sadly, the sequels promised by that snazzy subtitle were not to be. I don’t blame Beam or Konami for this, necessarily, as few 8-bit games were selling all that well circa 1992, especially downright weird ones. In any case, Nightshade’s one and only game appearance endures as a singular experience within the massive NES library.

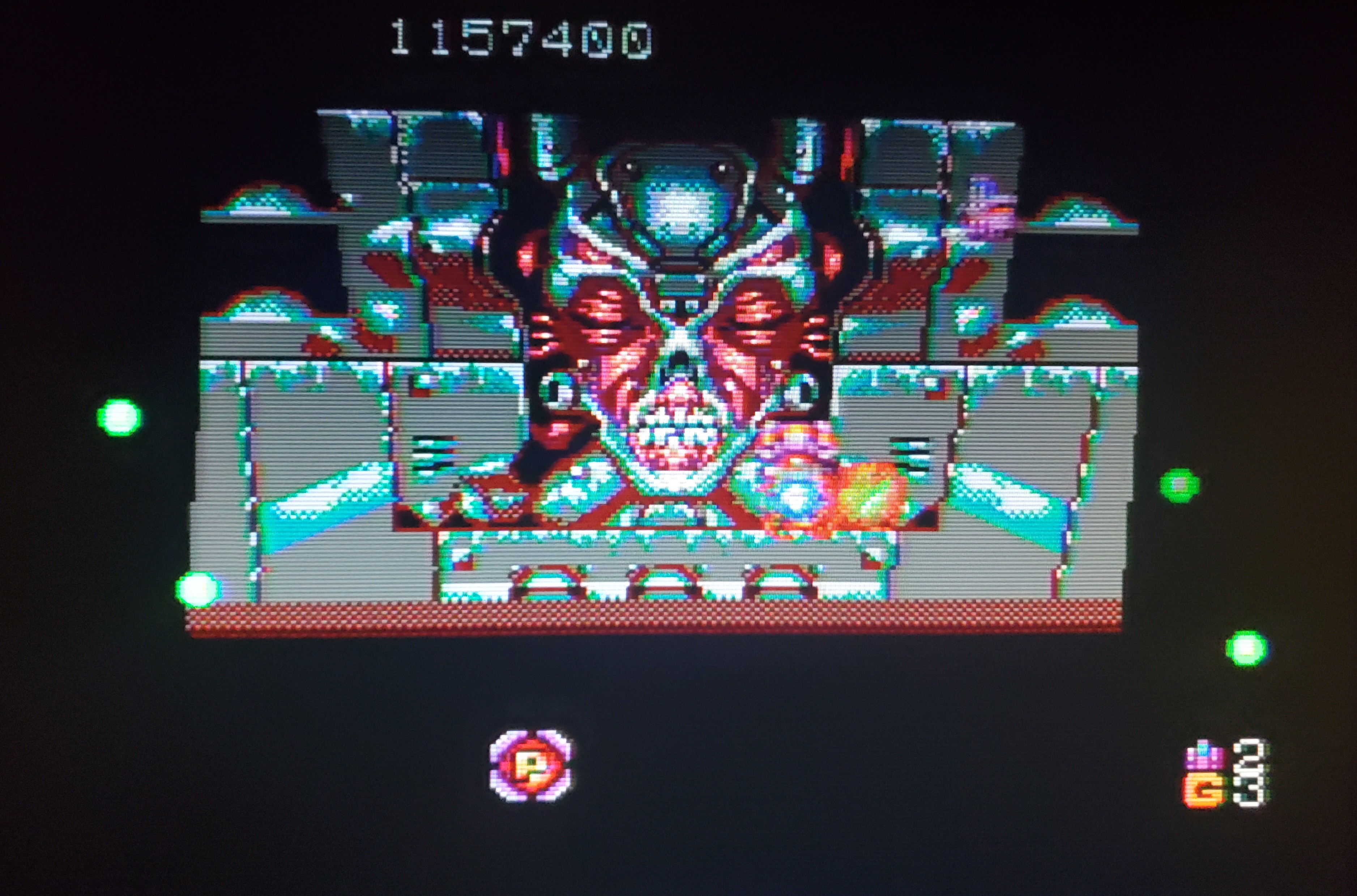

When Sutekh, Metro City’s reigning crime lord, manages to kill off veteran superhero Vortex, nothing stands between him and total domination. Nothing, that is, except for Nightshade, trenchcoated crime fighting alter-ego of mild-mannered encyclopedia researcher Mark Gray. Too bad old Nightshade isn’t off to the greatest of starts. As the game opens, Sutekh’s tied him to a chair next to a lit bomb. If he doesn’t think fast, his adventure could be over before it’s began.

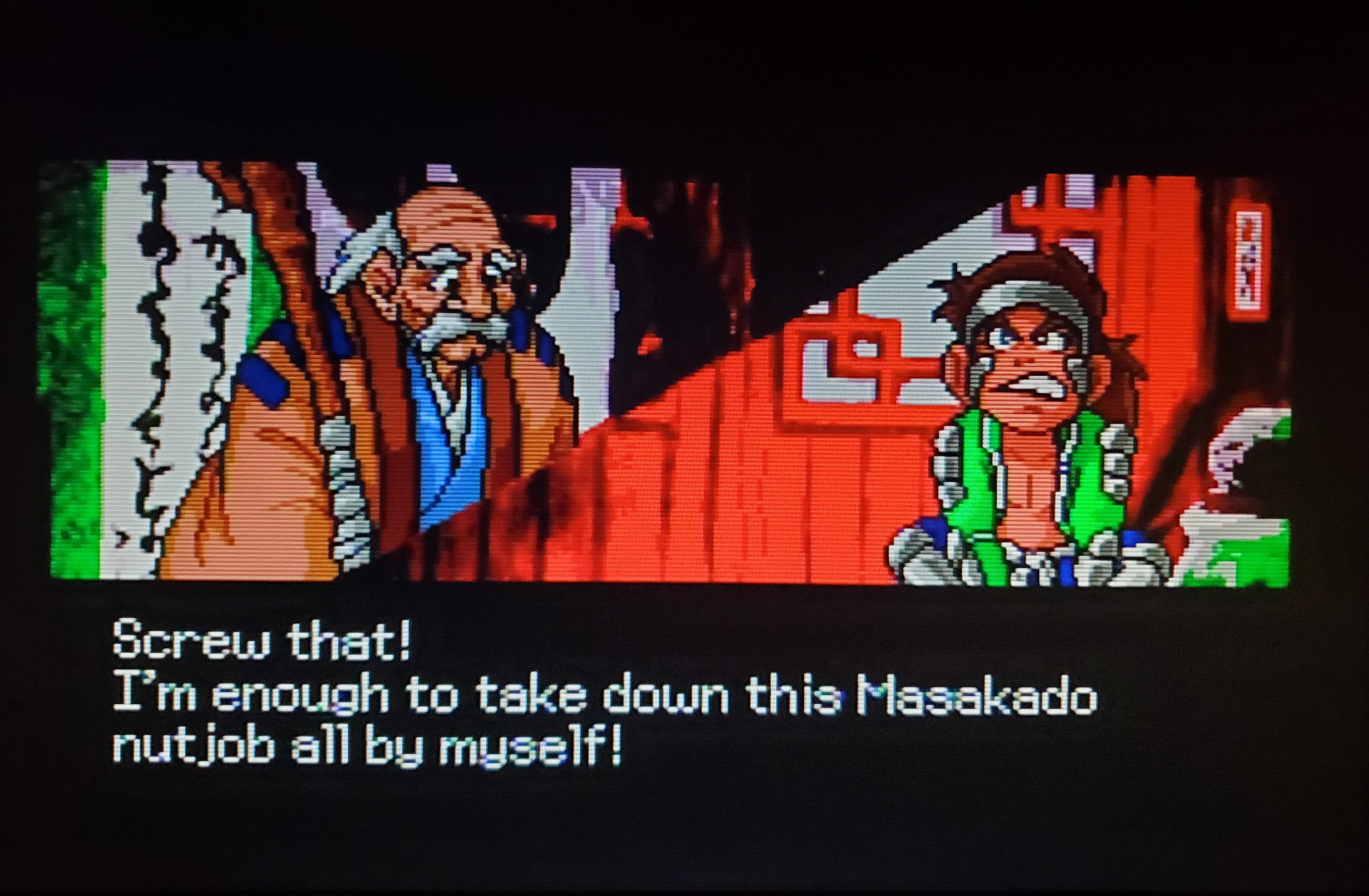

With its moody film noir-inspired opening music and cut scene, you might expect Nightshade to be quite the grim, gritty affair. Well, joke’s on you, because literally everything that follows is simply bananas; a full-blown pulp/comic hero parody in the vein of The Tick or The Venture Bros. A pretty good one, too, with plenty of sarcastic item descriptions, pop culture references, and recurring gags like various citizens of Metro City constantly mangling poor Nightshade’s name, dubbing him Lampshade among other things.

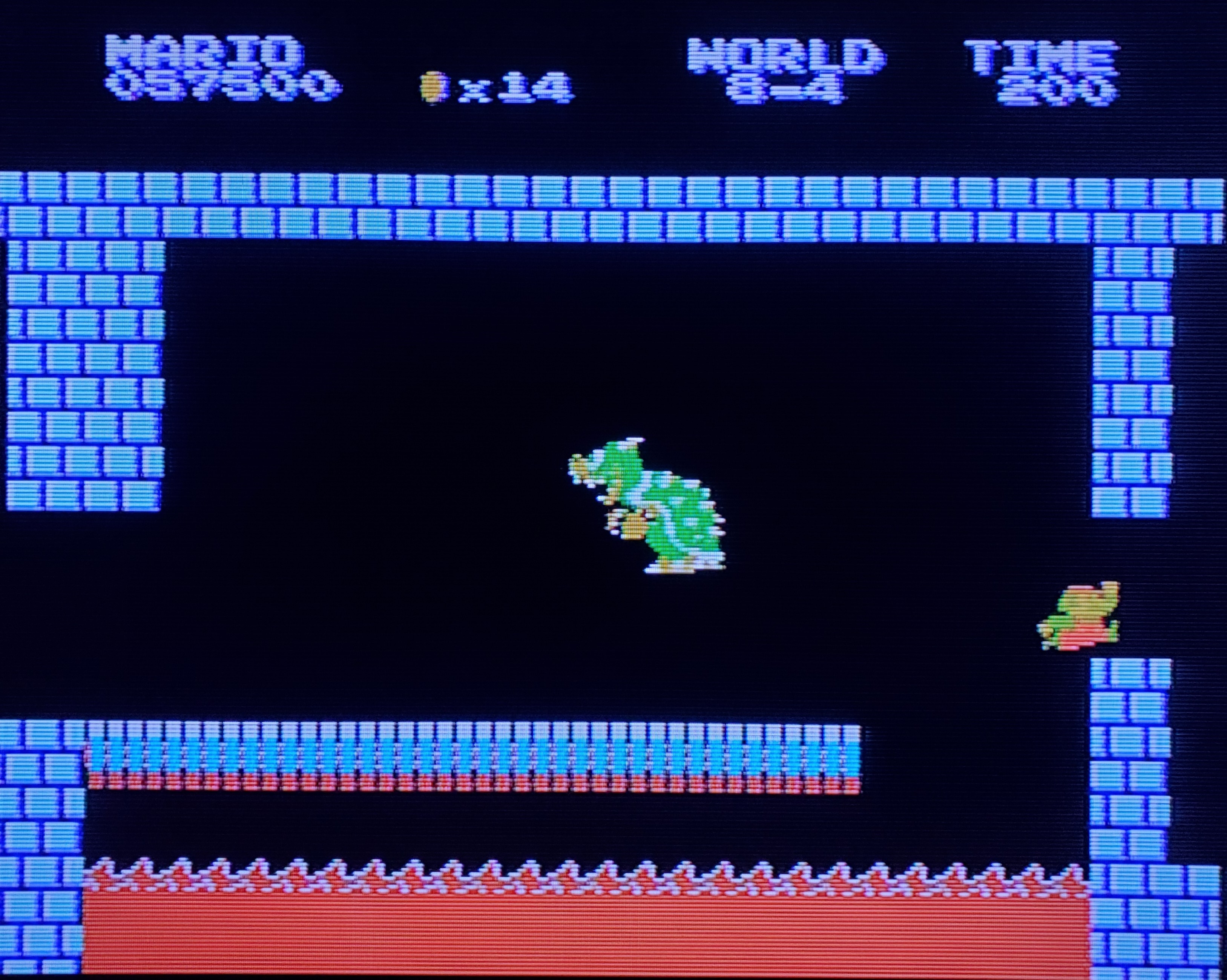

This slapstick sense of humor extends to the game mechanics proper. Each time Nightshade runs out of health, Sutekh show up to stick him in another overly elaborate death trap akin to the one from the opening scene. If Nightshade can manage to escape using a combination of quick thinking and accurate timing, he’s free to continue his mission. Otherwise, it’s game over and all progress is lost. The game also ends if he should reach the fifth and final trap, from which there is no escape. In other words, figuring out how to foil the traps gives you access to four extra lives.

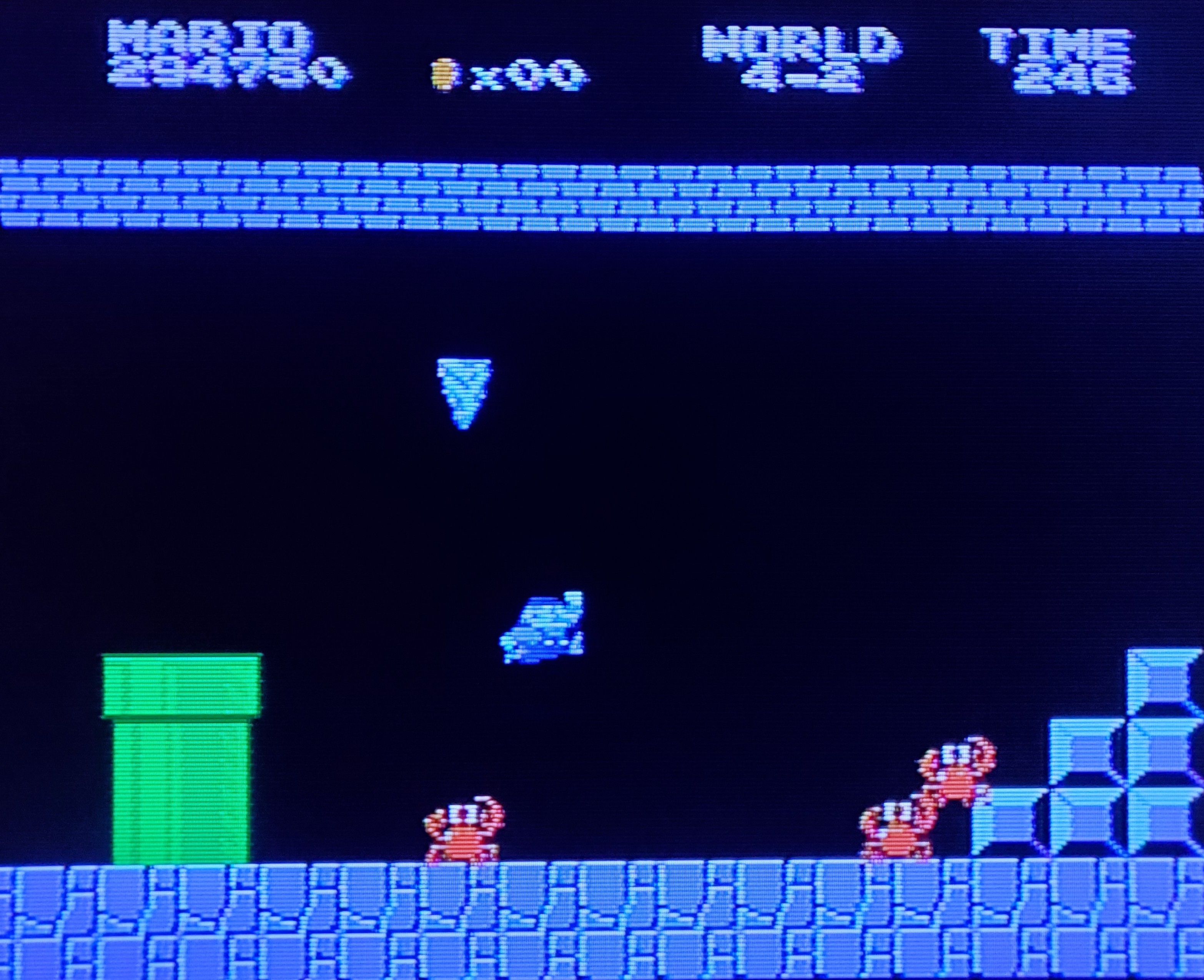

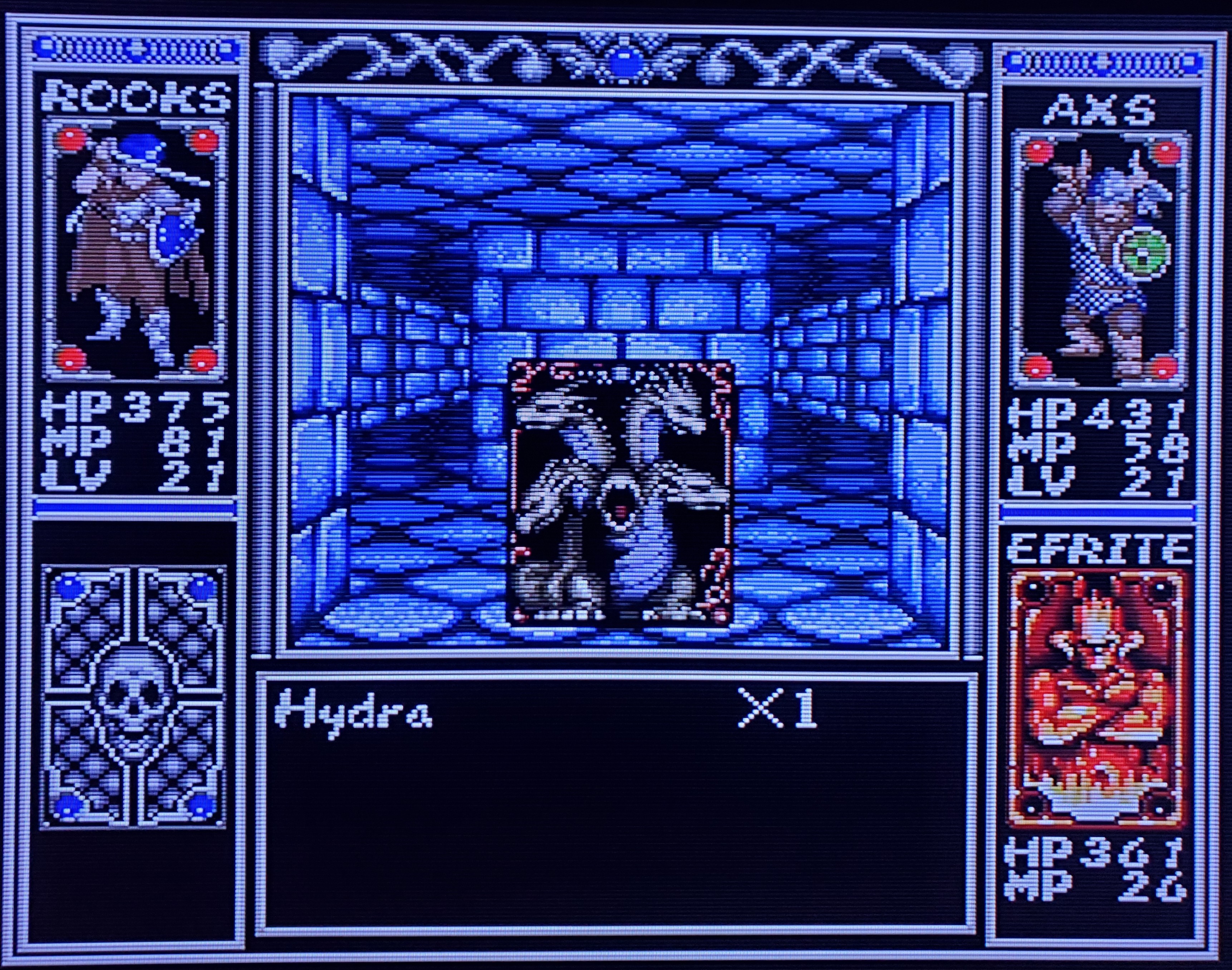

Most of your play time as Nightshade is spent wandering the city streets in a point-and-click adventure mode, summoning a cursor as needed to examine, pick up, and use various objects, speak to NPCs, and so on. Interfaces like this were rare on the NES, although not entirely unheard-of. See Maniac Mansion or Princess Tomato in the Salad Kingdom. What sets Nightshade apart is its combat, which uses a side-view beat-’em-up style. Although the contrast between the slow-paced, methodical exploration and the frantic brawls is theoretically exciting, I found the battles to be the game’s weakest aspect. Nightshade is slow on foot and has a high, floaty jump. Enemies tend to both be faster and enjoy greater hit priority on their attacks. True, most have exploitable weaknesses that can be mastered eventually, but the learning process is a painful one due to the sharply limited lives and healing resources. Needing to restart the game from scratch multiple times, redoing the early point-and-click segments over and over almost soured me on the game as a whole.

Almost. In the end, I’m glad I persevered through Nightshade’s mediocre fights and resulting early frustration. I was rewarded with a wild, witty escapade that absolutely merited more success than it found. On the plus side, some of its DNA did carry over to lead designer Paul Kidd’s 1993 follow-up project, Shadowrun for the Super Nintendo.