Forsooth, thou art most rad!

Now this takes me back. What can I even say about 1986’s Dragon Quest, better known here as Dragon Warrior? It was the first turn-based RPG for the Famicom/NES and consequently the first that many gamers of my generation, myself included, were ever exposed to. It’s ground zero for an entire genre in the minds of millions. The wilds of Alefgard are where I scored my first experience point, achieved my first level-up, and cast my first healing spell. This is primal stuff, man. Archetypal.

I can start by dispelling a few common misconceptions about the game. For starters, it was neither the first console RPG (1982’s Dragonstomper for the Atari 2600 is the best candidate for that honor) nor the first Japanese RPG (domestic creations like The Black Onyx and Dragon Slayer were staples on Japanese home computers as early as 1984). It also wasn’t designer Yuji Horii’s first major success. 1985 had seen the Famicom release of Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken (“The Portopia Serial Murder Incident”), Horii’s port of his own “visual novel” style detective adventure game originally released for home computers in 1983. In converting Portopia for Nintendo’s machine, Horii wisely avoided limiting the game’s appeal by forgoing use of the Famicom keyboard accessory and instead replacing the text parser of the computer versions with a menu of fourteen standardized commands that could be easily managed with the default controller. As the first adventure game released for the Famicom, Portopia moved over 700,000 units and ignited a passion for visual novels that persists in Japanese gaming circles to this day.

As a follow-up effort, Dragon Quest can be seen as a return to form for Horii: Start with a complex and potentially intimidating game type that’s popular on niche computers and then streamline and simplify it for introduction to the much wider and more lucrative console market. He took a cup of Ultima, added a dash of Wizardry, and then garnished with a user friendly interface straight out of Portopia. Two millions copies later, it was clear that lightning had indeed struck twice.

Well, two million copies in Japan, that is. Enix had equally high hopes for the North American release in 1989, for which Nintendo themselves would take over publishing duty. They went all-out by springing for enhanced graphics, a top notch localization of the game’s script, a battery save option to replace the original’s cumbersome passwords, and a detailed 64-page strategy guide bundled with every copy. It was a resounding flop.

What went wrong? Well, it turns out that much of the game’s initial success in Japan was due to its artwork by superstar illustrator Akira Toriyama and its heavy promotion in the pages of the popular action manga magazine Shōnen Jump. Over here, however, it was a totally unknown quantity to consumers and the result was warehouses full of unsellable Dragon Warrior cartridges. The solution? Another, more desperate stab at a magazine cross-promotion: Readers of Nintendo Power were actually sent a free copy of Dragon Warrior with every $20 subscription! An estimated 500,000 copies were distributed in this way. The hope was that, once they were exposed to the game one way or another, players in North America would be just as hooked as their counterparts across the Pacific and turn out in droves for the sequels.

Again, things didn’t quite work out as intended. Sales of Dragon Warrior II, III, and IV on the NES were all lukewarm at best. By the time Dragon Quest made the jump to 16-bit, Enix had given up entirely and the West wouldn’t see another entry in the series until Dragon Warrior VII made it to the PlayStation in 2001. In the meantime, Pokemon and Final Fantasy VII would step in and become the long-awaited smash hit “gateway” RPGs for the North American market, finally succeeding were Dragon Warrior had failed.

Don’t feel too bad for Yuji Horii and friends, though. Dragon Quest may still only hold cult appeal in my neck of the woods, but the mania it kicked off in its homeland has never truly abated. Even now, new releases are virtually national holidays in Japan and the franchise’s grinning blue slime mascot is as recognizable as Mickey Mouse.

Geez, that’s a lot of background. What about the actual game? Well, it goes like this: You start out in a throne room talking to a king. The king tells you that an evil dude called the Dragonlord has stolen the magic artifact that safeguards the land of Alefgard and kidnapped its beautiful princess to boot. Since you’re the descendant of a legendary hero, it’s now your job to gather the tools needed to breach the Dragonlord’s stronghold, introduce him to the pointy end of your sword, and recover the missing magical thingy. Also, that princess, if it’s not too much bother.

In order to do this, you need to explore the game’s medieval fantasy world from an Ultima style top-down viewpoint searching for important items and interrogating friendly villagers for hints on where to head next. Random encounters with monsters will shift the perspective to a first person combat display similar to Wizardry’s where you can choose your commands from a basic menu that includes options to fight, flee, cast magic spells, and use helpful items like medicinal herbs. These battles are very frequent and you’ll need to win hundreds of them in order to garner the thousands of experience points and gold pieces necessary to power your initially wimpy character up enough to stand a chance against the Dragonlord.

What’s that, you say? This sounds like every console RPG ever made? Bingo! When I called it archetypal, I wasn’t exaggerating. Dragon Warrior is the very mold, the template, the plain cheese pizza of JRPGs. This is what makes it so tricky to pin down three decades later. Even so, I’ll do my best to cover the highs and lows.

One thing that still stands out today are Toriyama’s stellar monster designs. Though I’ve never been able to find any enjoyment in his most famous creation, the Dragonball series, I’ve always been drawn to his “40% menacing, 60% adorable” take on traditional fantasy critters. Even when I was finally face-to-face with the fearsome Dragonlord himself, part of me wished I could rub his cute scaly belly instead of dueling to the death. The detail and charm packed into every foe’s portrait single-handedly justifies the choice of a first person view for the combat.

I’m also impressed by the sheer scope and quality of Dragon Warrior’s English translation and localization, which are credited to Toshiko Watson and Scott Pelland, respectively. Their work is years ahead of its time when you consider that the 1980s were the Wild West of game localization and many publishers couldn’t manage to produce so much as a single screen of translated text that didn’t read like drunken Mad Libs. Here, all the dialogue makes sense and the faux Elizabethan dialect the characters speak with is profoundly corny, but endearingly so. I’ll even admit to finding it pretty epic as a kid. There’s also a sweet extended in-joke included in the form of some character cameos that will be very familiar to former Nintendo Power readers.

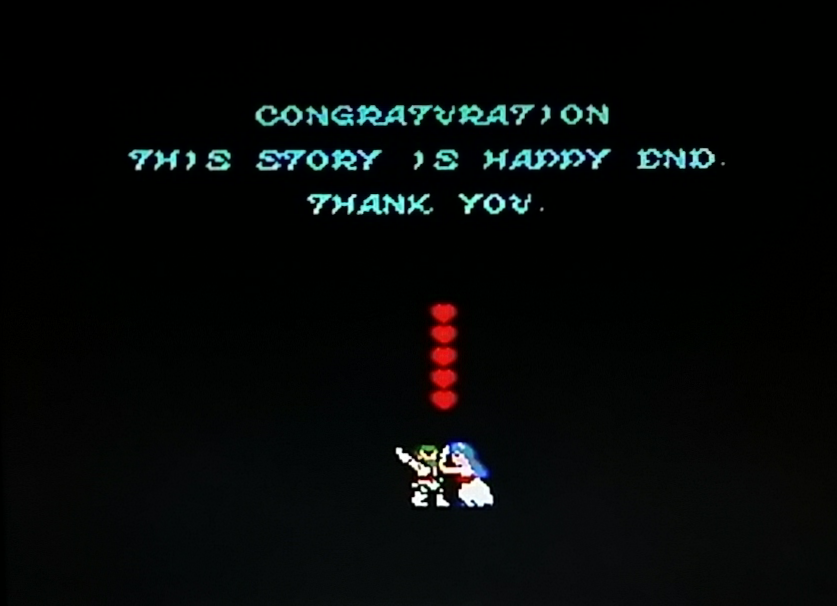

If there’s one undeniable downside to playing through Dragon Warrior, it’s the extraordinary amount of mindless grinding required. While almost all RPGs expect the player to engage in endless random battles for money and experience, the best of them also give you plenty of places to go and things to do along the way. That way, you never have a chance to dwell on how repetitive these frequent combats can be on their own. Unfortunately, there are no side quests or diversions to be found here. Dragon Warrior has exactly two goals for the player: Kill the Dragonlord and rescue the princess. The game world is also quite small, which makes gathering the three key items needed to enter the Dragonlord’s castle is a simple task if you know where to look. The end result? About two hours of worthwhile exploration and excitement aggressively padded out into an excruciating 10+ hour slog. The late game in particular is a mess. By level 15, I had tracked down every key item, acquired all the best equipment, and even rescued the princess. There was literally nothing left in the entire game for me to do except kill the Dragonlord…which requires you to be around level 20. Reaching level 20 requires a total of 26,000 experience points, well over twice what I’d accumulated up to that point. So, stubborn fool that I am, I spent hours pacing back and forth over the same stretch of map, robotically striking down hundreds of generic enemies and pausing only to trek back to the inn when I ran low on healing spells. Then I killed the Dragonlord. Such fun.

Don’t get me wrong: As an introductory RPG circa 1986, Dragon Warrior’s approach is nothing short of genius. Horii managed to pare away every non-essential element from the popular computer RPGs of the time while still retaining the core appeal of a grand fantasy adventure where the player’s avatar continually grows in power and sharp wits and sound decisions matter more than quick reflexes. There’s no character customization to be found here, no class system, no multiple character party to manage, and the story is the most basic “princess and dragon” setup imaginable. This not only ensured that the game had the broadest possible appeal, it perfectly set up Dragon Quest as an ongoing series, since follow-up releases could be predicated on gradually reintroducing these very same advanced mechanics in modular fashion. Thus, the second game included multiple player characters, the third added character creation and a robust class system, and so on. In this way, the series both birthed and raised a generation of Japanese RPG fans.

Dragon Warrior captivated me back in 1989. I played it day and night and even wandered its perilous fields and dungeons in my dreams. Next came Final Fantasy, tabletop RPGs like Dungeons & Dragons, and so many more. Revisiting it now, though, I’m reminded why I mainly play action games these days. While the presentation still has its charms, it’s clear that my elementary schooler self didn’t value his time very highly. Simple and repetitive as it is, Dragon Warrior is best approached today as either a nostalgia trip or an interactive history lesson. In either case, patience is a must. RPG fans in general are much better off seeking out the later re-releases for the Game Boy Color and Super Famicom, which both cut down on the grinding significantly. That, or skipping straight to the brilliant Dragon Warrior III.

Thou hast been warned!